The Rochester Crime Family was an Italian-American organized crime syndicate based in Rochester that existed, in a centralized organized form, from roughly 1950 to 1993. Part of the American Mafia, or La Cosa Nostra, the Rochester Crime Family can trace its roots to various Italian-American crime groups, notably the Black Hand, a Camorra racket of the early 20th century, and later Buffalo's ![]() Magaddino Crime Family, of which the Rochester family has direct lineage.

Magaddino Crime Family, of which the Rochester family has direct lineage.

History

There is conflicting information about where and how the Rochester Crime Family came to be. One of the last mafia families to seize control over the underworld of an American city, Rochester's crime syndicate had ties to Buffalo, Bonanno and Pittsburgh crime groups prior to gaining autonomy. Due to the secretive nature of the Italian-American Mafia and its sacred oath of omertà, the true history may never be uncovered. According to the FBI and those in the know, Rochester became an independent family following an internal power struggle in Buffalo that caused a split in their family sometime between the 1950s and early 1960s. Most of Rochester's organized crime activity was home grown, however, and begins where many other La Cosa Nostra families do, among early 20th century Italian immigrants.

Roots

Downtown Rochester as it appeared in the 1930s, when organized crime was hidden and rampant

Downtown Rochester as it appeared in the 1930s, when organized crime was hidden and rampant

When Italian immigrants began entering the United States, Rochester was one of the top destinations for settlers outside of New York City due to its then-thriving economy, factory jobs and modern housing. Those who were less fortunate continued their criminal activities from Italy when they came over, and much of that included extortion. The "Black Hand" was the name given to a general group of Italian immigrant extortionists who appeared in the early 1900s throughout the Northeast. They were mostly small street gangs, but played a major role in the organization and strengthening of what became the mafia. In Rochester, there were several notable cases of the Black Hand striking locals. The ![]() Barrel Murder of 1911 was an infamous case at the time in which Black Hander Francesco Manzello was found brutally murdered and decapitated, then stuffed into a barrel and dumped near Irondequoit Bay. In March 1919, an alleged Black Hand member named Luigi Guadagnino shot and killed Rochester Police Officer James H. Upton in cold blood on South Plymouth Avenue near Tremont Street after being caught setting fire to a fruit store, no doubt because the owner of the fruit store had failed to give in when money had been demanded from him. In May 1921, Guadagnino was arrested, put on trial and quickly convicted after he pled guilty to second-degree manslaughter. These are just some example of the early days of organized crime in Rochester.

Barrel Murder of 1911 was an infamous case at the time in which Black Hander Francesco Manzello was found brutally murdered and decapitated, then stuffed into a barrel and dumped near Irondequoit Bay. In March 1919, an alleged Black Hand member named Luigi Guadagnino shot and killed Rochester Police Officer James H. Upton in cold blood on South Plymouth Avenue near Tremont Street after being caught setting fire to a fruit store, no doubt because the owner of the fruit store had failed to give in when money had been demanded from him. In May 1921, Guadagnino was arrested, put on trial and quickly convicted after he pled guilty to second-degree manslaughter. These are just some example of the early days of organized crime in Rochester.

When Prohibition was passed in 1920, the underworld centralized power all across the United States, and Rochester was no exception. Bootlegging gangs would become prominent and eventually large scale mafia families would begin to make their mark on the city. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, gambling, counterfeiting, bootlegging and extortion were common activities and there were several "liquor wars" between street gangs that resulted in a power struggle. This was a bloody period during which many gang members were killed or kidnapped. The leader of the street gangs during this early period was likely Alfio Boscarino, an Italian immigrant who was dubbed "king of the bootleggers" by local newspapers. Boscarino was allegedly the proprietor of dozens of redistilling plants and controlled the flow of illegal alcohol. Several attempts were made on his life, escaping gunfire from rival gang members every time with minor wounds, he was memorialized as "Alfio the lucky" when he died in 1961 of natural causes due to his constant successful escapes from certain death. Ties to the Chicago Outfit were rampant as well until the repeal of prohibition. Many other players in the street wars during this time were parents or close relatives of notorious mafia leaders of the later Rochester family including Vito Piccarreto and Pasquale Amico, who may have been the first "leader" of rackets in Rochester.

Pasquale Amico was the a veteran mobster from the prohibition era who ran bootlegging operations and other underworld activities throughout the early days of organized crime. Amico had the support of the Buffalo Crime Family and Rochester's ties to the Buffalo family are very likely rooted in Amico's relationship with figures from that area. In 1931, Pasquale Amico was arrested with two other men leaving the home Angelo "Buffalo Bill" Palmeri, the leader and founder of La Cosa Nostra in Buffalo. Also arrested with Amico was Joseph "The Wolf" DiCarlo Jr., another Buffalo mobster who was labelled "public enemy number one" by the local media at the time. This relationship with top ranking member of the underworld to the west was noticed by law enforcement and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics kept a close eye on him until his death in 1947. Little information has been confirmed about this period preceding the 1950s, however it is widely accepted that criminal elements remained controlled by Buffalo as Stefano Magaddino gained and consolidated power.

Consolidation

On November 14, 1957, mafia members from all over the United States, Italy and Cuba met in a summit at Joseph Barbara's estate in Apalachin, New York. During this meeting, which was called by Vito Genovese and ![]() Stefano "The Undertaker" Magaddino, local law enforcement became suspicious of the expensive luxury cars congregated in the small village and raided the meeting, resulting in the arrests of over sixty mafioso from around the country. The Apalachin Meeting became notorious for blowing the lid off of Italian-American organized crime, which was once thought of as fictitious. Among those arrested were about a dozen Western New York gangsters. Following the raid, the FBI began to heavily monitor suspected crime figures and in 1963, Joseph Valachi, a mobster himself, testified before the United States Senate on the existence and state of the American Mafia. During his testimony, Valachi identified by name Frank Valenti and Constanze "Stanley" Valenti, two Rochester brothers who were arrested at the Apalachin Meeting, as made men and alleged that the Buffalo Crime Family controlled most of Upstate New York, including Rochester, Syracuse, Utica and even parts of Ontario, Canada.

Stefano "The Undertaker" Magaddino, local law enforcement became suspicious of the expensive luxury cars congregated in the small village and raided the meeting, resulting in the arrests of over sixty mafioso from around the country. The Apalachin Meeting became notorious for blowing the lid off of Italian-American organized crime, which was once thought of as fictitious. Among those arrested were about a dozen Western New York gangsters. Following the raid, the FBI began to heavily monitor suspected crime figures and in 1963, Joseph Valachi, a mobster himself, testified before the United States Senate on the existence and state of the American Mafia. During his testimony, Valachi identified by name Frank Valenti and Constanze "Stanley" Valenti, two Rochester brothers who were arrested at the Apalachin Meeting, as made men and alleged that the Buffalo Crime Family controlled most of Upstate New York, including Rochester, Syracuse, Utica and even parts of Ontario, Canada.

According to the FBI, at the time of the Apalachin Meeting, Stanley Valenti was a member of the Buffalo Family running organized crime in Rochester, at the helm of gambling, prostitution and extortion that fueled a powerful street economy within Monroe County. The fallout from the bust included intense federal surveillance on the Valenti brothers. This hurt their opportunity to make any moves. When Stanley Valenti was arrested in 1957, he refused to cooperate with authorities and was sentenced to 16 months in prison along with his brother Frank Valenti who was initially briefly jailed and subsequently returned to his native Pittsburgh to work for LaRocca. In the absence of a leader another longtime crime figure with the backing of Buffalo seized control. Jacomino Russolesi, a Buffalo capo better known as Jake Russo, became boss of Magaddino's Rochester crime branch in 1958. Despite being given control of the city, Russo was looked at as a weak leader unable to control his soldiers. In 1961, Canadian mobster and heroin smuggler Albeto Agueci was found murdered outside of Rochester. It is believed that Russo was responsible for the hit under Buffalo's orders as Agueci was planning on killing Stefano Magaddino. In wake of the Valachi Hearings in 1963, Russo's weak reputation caused him to fall out of favor with Magaddino as he was unable to control unaffiliated gamblers from encroaching on the territory, causing the beginnings of the fissure that would break Rochester off from Buffalo to begin.

In 1964, Frank Valenti returned to Rochester after laying low in Pittsburgh, bringing along with him his brother and former leader of Rochester Stanley Valenti and Pittsburgh associate Angelo Vaccaro. Frank Valenti had spent the last few years working in the underworld of John LaRocca's ![]() Pittsburgh Crime Family and his brother married the daughter of a Pittsburgh capo. This ignited some tension between Rochester and Buffalo as Magaddino perceived this as a shift in allegiance to another family.

Pittsburgh Crime Family and his brother married the daughter of a Pittsburgh capo. This ignited some tension between Rochester and Buffalo as Magaddino perceived this as a shift in allegiance to another family.

Shortly after his return around November of 1964, Frank Valenti threw two massive parties, including one at Eddie's Chop House, crowning himself the new boss of Rochester. He was overheard telling guests he was now "the man to see in Rochester." Notably, Jake Russo was not invited to these parties as he mysteriously disappeared just days prior. Russo was never heard from again, presumably murdered by Valenti loyalists, and his body was never found. At this point, Valenti solidified power and became the undisputed leader of organized crime in the city.

Valenti Regime

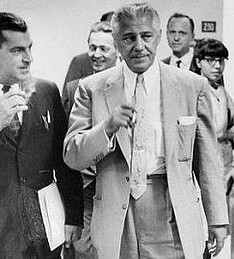

Frank Valenti was Rochester's first official godfather.

Frank Valenti was Rochester's first official godfather.

Frank Valenti's flashy return to rule over Rochester was much in line with his own personality. Valenti was well known throughout the city for his dapper appearance, expensive suits, slicked back hair, gold watches and swanky aura. Unfortunately for the mob however, this lifestyle would only begin to draw attention to organized crime as the Democrat & Chronicle began to publish a serious of exposés detailing Valenti's criminal past. Frank was nicknamed "The Sphinx" due to his stone cold, expressionless facial expressions when interrogated by police. Authorities, however, were certainly well aware of his business. Around New Years 1965, a serious of gambling raids took down some mafia operations controlled by Valenti. Suspecting an informant, Valenti ordered the murder of Dominick Allocco, a well known gambling figure who was suspected by Valenti of ratting. Police questioned Valenti about the slaying, but were unable to prove his guilt and he was set free, signaling the extent of his power. Also murdered would be gambling czar "Johnny Broadway" Cavagrotti, an old Russo loyalist who failed to fall in line when Valenti took control. He was kidnapped and killed to send a message to dissenters. To prevent future law enforcement raids, Valenti turned to bribery and held a meeting with members of the Vice Control Unit of the Rochester Police Bureau. A later investigation concluded this meeting was “certainly not for any legitimate law enforcement purpose or for the carrying out of any lawful and proper police function”. It was only the first of a series of corruption scandals and strange behavior surrounding Rochester law enforcement agencies and the mafia.

As the 1960s went on, Rochester's underworld grew. Frank Valenti already held an extensive criminal history and he would use the relationships he built over the last several decades to aid him in his takeover of Rochester. Some of the well known mobsters in his circle included the aforementioned John LaRocca and Antonio Ripepi of Pittsburgh. He also formed relationships with Michael Genovese, Joseph Bonnano, Joseph Profaci and Angelo Bruno. It was also during this time that Valenti began to appoint an underboss and consigliere as the family became more structured and power was consolidated. There were now more made members than ever before. Gambling became the mafia's main source of income during this period and was expanded even beyond Rochester to Las Vegas, Niagara Falls and Atlantic City. Naturally, raids on these illegal gambling joints became a common occurrence, but hardly deterred the mobsters from operating. Valenti sought to expand organized crime operations from Rochester to other areas, modelling his growth off Buffalo's success. One such scheme involved the takeover of vending machine businesses in the Syracuse and Binghampton areas, which was a collaboration between Rochester and Russell Bufalino's Scranton Crime Family. Drug dealing, too, increased and infiltration of labor unions also became a staple under Valenti.

Independence From Buffalo

In 1968, Stefano Magaddino was arrested with his brother Peter for interstate bookmaking. A subsequent raid of his son's home in Niagara Falls uncovered a suitcase filled with several hundred thousand dollars in cash. The now aging Magaddino was now faced with animosity among his underlings. Shortly following his arrest, several Buffalo capos met at Frank Valenti's farmhouse outside of Rochester to discuss the future of the family. Among those in attendance were Sam Pieri and Joseph Todaro Sr. who decided to oust Magaddino from Buffalo. With the backing of the Pittsburgh Crime Family's Antonio Ripepi and with the blessing of Buffalo's capos now hostile towards Magaddino, Valenti declared Rochester an independent family that would no longer answer to Buffalo. As a newly autonomous family, La Cosa Nostra in Rochester was now headed by a strong hierarchy with Frank Valenti as the boss, Samuel "Red" Russotti as his underboss, Rene Piccarretto as official adviser or "consigliere" and various capos Salvatore "Sammy G" Gingello, Dominic Celestino, Thomas DiDio, Angelo Vaccaro and Dominic Chirico who oversaw day to day operations on the streets. This became the height of the Valenti regime as he now had total control over the city.

The Columbus Day Bombings

Assassinations became a method of showing muscle in Valenti's Rochester. Throughout the late 1960s, multiple high profile murders began to draw attention of law enforcement towards the mafia. Samuel C. Russotti, the nephew of Valenti's underboss was found dead with multiple gunshot wounds to the head. Also killed were Norman Huck and Enrico Visconte. In 1970, capo Salvatore Gingello collected over one hundred thousand dollars in deposits for a gambling junket to Las Vegas, but the money vanished. Both Gingello and underboss Russotti blamed William "Billy" Lupo, a loanshark and former Jake Russo associate who was one of Valenti's most trusted men. The accusation, never determined to be true, may have been a sign that he was becoming hostile towards Valenti. When authorities found Lupo's body slumped over the wheel of his car on a dead end street, robbed of his cash, it was discovered he was under federal investigation into loansharking and turned their attention toward the Rochester Crime Family.

Assassinations became a method of showing muscle in Valenti's Rochester. Throughout the late 1960s, multiple high profile murders began to draw attention of law enforcement towards the mafia. Samuel C. Russotti, the nephew of Valenti's underboss was found dead with multiple gunshot wounds to the head. Also killed were Norman Huck and Enrico Visconte. In 1970, capo Salvatore Gingello collected over one hundred thousand dollars in deposits for a gambling junket to Las Vegas, but the money vanished. Both Gingello and underboss Russotti blamed William "Billy" Lupo, a loanshark and former Jake Russo associate who was one of Valenti's most trusted men. The accusation, never determined to be true, may have been a sign that he was becoming hostile towards Valenti. When authorities found Lupo's body slumped over the wheel of his car on a dead end street, robbed of his cash, it was discovered he was under federal investigation into loansharking and turned their attention toward the Rochester Crime Family.

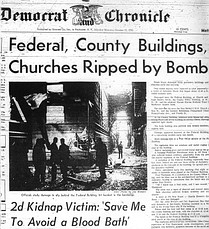

In an elaborate plan to draw attention away from the Rochester family, Valenti ordered a special team to detonate bombs at various locations throughout the city. On October 12, 1970, bombs exploded and caused major damage to two black churches, the Monroe County Office Building, the U.S. Federal Courthouse and the home of a union official. Perhaps plausibly at the time, police suspected anti-Vietnam War protesters or other radical groups and shifted resources away from La Cosa Nostra. Authorities had virtually no insight into how or why these explosions occured, other than a report that men stole eighty nine sticks of dynamite from a construction site in Brockport in the days preceding. Surely unbeknownst to those who had planned this attack, the bombings came just days after several other bombings in other cities throughout the country and a federal investigation into bomb threats was launched immediately. Amazed that his plan had succeeded, Valenti ordered further bombings to three synagogues and the home of a federal judge. Noticing there was no pattern or direct target, investigators were now entirely focused on solving the bombings. Valenti likewise succeeded in intimidating his enemies who now understood he was relentless.

Power Struggle

Resenting the viciousness of their godfather, members of the Rochester Family began to turn on Valenti following the bombings. In 1972, he was approached by both underboss Russotti and consigliere Piccarreto asking him to step down, accusing him of skimming profits and keeping for himself. His underlings demanded he return the money or abdicate power, however Valenti refused. Later, Valenti felt disgraced but did return the money. He however also wanted to punish his men for this, therefore he ordered his trusted capo Dominick Chirico to organize a hit against capo Gingello, as well as Russotti and Piccarreto. However, to murder made members of the mafia Valenti had to get permission of the other families, including the Pittsburgh and Bonanno crime family, under house sanction his organization operated. The answer was no. Russotti, Gingello and Piccarreto were safe but had heard of the plot against them and were out for revenge. They went to see Bonanno family officials, with whom Piccarreto was close, to have their support in the removal and probable murder of Valenti, but they're request was also turned down due to Valenti's connections to the LaRocca crime family of Pittsburgh. Although they weren't allowed to kill Valenti, they still wanted to have revenge. To achieve this, the trio murdered Dominick Chirico, a loyal Valenti capo. He was killed by a shotgun blast on June 5, 1972 on Raines Park, in the city's Maplewood neighborhood, outside the home of his girlfriend. Chirico's slaying would prove to be devastating to the spurned Rochester boss. He was one of the most loyal captains in the family, serving as both a personal bodyguard and member of Valenti's "special crew." Tensions inside the Valenti family were now running high. Following the murder of Chirico, a meeting took place between the top members of the mafia shortly before midnight on June 5, 1972 where Frank Valenti agreed to retire to Arizona, where he had already been purchasing property.

On December 15 of the same year Valenti was convicted of extortion in a case involving a building contractor in Batavia. The Valenti's were now officially out of Rochester and their ties to the Pittsburgh crime family slowly vanished. Samuel "Red" Russotti became the new boss of Rochester with "Sammy G" Gingello as his underboss. Rene Piccarreto retained his position as the family adviser. Following his conviction, Frank Valenti and his brother Constenze Valenti went to live in Arizona, where they died in 2008 and 2001 respectively.

Russotti Era

Russotti became the don of the Rochester family in the 1970s.

Russotti became the don of the Rochester family in the 1970s.

Former underboss Samuel Russotti succeeded Frank Valenti as the boss of the Rochester Crime Family in December of 1972. Apart from some slight reorganizing, notably appointing Salvatore "Sammy G" Gingello as his underboss and booting Valenti loyalists from the city, the Rochester underworld continued to operate much as it had during his predecessor's reign. Stronger than ever though, Russotti, nicknamed "Red" for the color of his hair as a young man, ruled as a strong godfather, leaving most of the muscle to his captains. To the general public however, he portrayed a friendly and grandfatherly persona, often waving to police officers who were conducting surveillance on him and smiling for photographs taken by the media. This would prove to be the peak of the Rochester Crime Family, at least in raw numbers. It is estimated that roughly 45 men were made members of the mafia clan, and hundreds, perhaps thousands, of associates assisted in procedures. Long practiced tactics continued with gambling at the helm, although the new group was fond of bid-rigging, bribery and extortion, aiming for more government construction contracts than previously held. Russotti's rule would begin bloody however when in November 1973, authorities discovered the body of Vincent "Jimmy The Hammer" Massaro in the trunk of his car.

Vincent Massaro was an enforcer and hit man who specialized in arson. His history with the family was mainly inconsiderable, but he performed various duties for wiseguys in and around Rochester. The night of his murder, Massaro received a call from his close friend Angelo Monachino, luring him to the garage of a construction company in Brighton. He was overheard on the phone yelling "I'll straighten that son of a bitch out" before leaving with a loaded pistol. By the time he arrived at the garage, he must've sensed something was wrong because he reached into his pocket and fumbled for his gun. Before he could respond, Jimmy The Hammer was shot, his close friends Angelo Monachino and Eugene DiFrancesco emptied a clip into his face and stuffed his body into the trunk of his own car. Massaro was murdered for complaining about activities of the mafia's leadership to criminals outside the family and taking jobs from other gangs. This was the first major hit of Russotti's reign, who ordered the slaying because Massaro dared to speak to outsiders, and probably as a show of force to others who dared cross the new don. Fed up with mob activity, law enforcement started to spend more time on cracking the case, but nobody was talking and it appeared the case would go unsolved like so many other slayings. However by 1975, Rochester police had arrested several low level mob associates and extracted valuable information from them that would lead to a major bust of organized crime. Among those arrested was Angelo Monachino, who made the decision to flip and become a government informant rather than face thirty four federal indictments. He and others were placed into the witness protection program. Upon interviewing their informants, police learned the truth behind various gangland murders, unsolved arsons, the Columbus Day Bombings and of an alleged plot to assassinate Monroe County Sheriff William Lombard. These revelations, especially the latter, angered law enforcement officials, who now had a personal vendetta to take down the mafia.

Arrests & Law Enforcement Scandal

Following the revelations of the bombings and plot to kill the sheriff, police arrested the entire upper echelon of the Rochester Crime Family. Boss Samuel "Red" Russotti, underboss Salvatore "Sammy G" Gingello, advisor Rene Piccarreto, capo Thomas Marotta, and soldier Eugene DeFrancesco were all arrested and charged with the murder of "Jimmy The Hammer" Massaro. It wasn't just the leaders however, even members of the mafia's middle tier were apprehended and charged with crimes stemming from the revelations of the government witnesses. Showing widespread local corruption, some of the arrested included union leader Samuel C. Campanella, teamster Anthony Gingello, lawyer Samuel J. DiGaetano, Rochester Fire Chief Joseph Nalore and mafia capo Richard Marino, all of whom played various roles in these high profile crimes. The information provided by the cooperating witnesses was corroborated with extensive surveillance reports of the Monroe County sheriff department. The case against the mobsters was strong, highly publicized and revealed the inner workings of the mafia in Rochester. Famed lawyer F. Lee Bailey represented Gingello, while others hired prominent attorneys to defend them. The evidence presented by the prosecution was too damning though, and in November 1976, resulted in the conviction of almost all of the original defendants. Russotti, Piccaretto, Gingello and three others received lengthy prison sentences in January 1977. It was the first major success against the Rochester mob since Valenti’s conviction and marked the first time anywhere in the nation that the leadership of an organized crime family were all convicted at the same time.

Imprisoned, power was left in the hand of various associates and soldier Thomas DiDio was named acting boss in Russotti's absence.

Unfortunately for the police, allegations of perjury during the Massaro trial sparked an investigation into the Monroe County Sheriff Department. One of the biggest mafia convictions in history would quickly turn into one of the biggest law enforcement scandals in the war on organized crime. Ultimately it was determined that not only did police lie, but they were also guilty of entrapment and fabricating evidence presented in the trial that led to the convictions. When in January 1978 a sheriff department detective admitted to this in Federal Court, the convictions of Russotti and his confederates were immediately overturned. On February 1, 1978, all were released from prison, after having served a little more then one year. The actions of the sheriff’s department would have consequences for several of its own members including a brief jail sentence for Rochester Police detective William "Backroom Bill" Mahoney. The disgraced official was found guilty of not only fabricating evidence to take down the mafia, but also was uncovered later to be notorious for beating suspects in interrogation rooms and forcing them to sign false confessions. With the mobsters released from prison and back in power, police were back to square one.

While in jail, acting boss Thomas DiDio was instructed to keep business in the hands of associates and to take care of the families of the imprisoned mafia leaders. By all accounts that didn't happen and by the time Russotti returned home, tensions were fuming. Believing he would be easily controlled, appointing DiDio would prove to be one of Russotti's most fatal missteps as Thomas DiDio now refused to step down as acting boss, which would fuel a bloody street war.

A/B Team Wars

In an attempt to strengthen his position, DiDio reportedly sought the advice of Stanley Valenti, who in turn consulted his brother. Frank saw the split as an opportunity to regain his former power upon release from prison. DiDio was advised that the Valentis were behind him. He was also promised the support of Pittsburgh's mafia with the stipulation that it would only come if they were successful in overthrowing the leading faction. Through this outreach he earned the allegiance of several mobsters including Ross Chirico, looking to avenge his slain brother Dominick's death, and Angelo Vaccaro. Towards the end of 1977, DiDio and his followers were confronted by Russotti's close friend and teamster official John "Johnny Flowers" Fiorino, who relayed the message that the old guard was coming home and it was time for him to go. Fiorino beat the renegade group to a bloody pulp and forced them into hiding just as Russotti returned to Rochester. Both law enforcement and the media had followed these developments on the street with interest. The main players of the factions were quickly identified, and popularly dubbed the “A-Team”, those loyal to Russotti, and the “B-Team”, the Valenti and DiDio supporters. The inevitable struggle that would follow therefore became known as the “Alphabet War."

Assassination of Sammy G

Salvatore 'Sammy G' Gingello was one of Rochester's most notorious mobsters who met an early demise in a car bomb.

Salvatore 'Sammy G' Gingello was one of Rochester's most notorious mobsters who met an early demise in a car bomb.

Salvatore "Sammy G" Gingello was arguably the most colorful of Rochester's mobsters. Well known, well liked and well respected on the streets, Gingello carried with him a command of deference and to many, despite never officially being named boss, he was seen as the face of the Rochester Crime Family. "Sammy G" was a Russotti loyalist and underboss, often seen at Rochester's finest restaurants, nightclubs and social clubs, always wearing the most luxurious suits, driving the finest cars and often with a beautiful woman at his side. Stories of Gingello entering an establishment and purchasing rounds of drinks for dozens of strangers were common examples of his generosity, but contrasting stories of his foul temper and violence provided a glimpse into his ruthlessness. Nonetheless, Gingello was considered by many the glue that held Rochester's family together. As the struggle for power in Rochester geared up, Gingello employed two bodyguards, mob enforcers Thomas Torpey and Thomas Taylor to provide muscle as needed during Sammy G's outings. The face of the A-Team, he was quickly targeted by B-Team members who repeatedly attempted to kill him on numerous occasions.

As the number one target in the "Alphabet Wars," more than five attempts were made on Gingello's life by DiDio's B-Team. The reason he was such a target to the insurgent mafia group was the belief that if Gingello fell, chaos would ensue, Russotti's loyalty would fall out of favor of his men, and DiDio's group could pick up the pieces to achieve power. During the planning sessions to kill Gingello, the suggestion came up to lower a bomb down his chimney. This plan was quickly discarded when a review of his home revealed that the house didn’t have a chimney. A second plan to plant the bomb in a child’s Big Wheel in front of the house was dismissed as being too risky to neighborhood children. Another try at using an explosive device failed in the midst of a high speed chase and shooting between opposing mobsters, when the bomb fell off the B-Team member's car during transport and was turned over to police by a 12 year old boy. Considered too, was detonating a bomb inside a traffic cone as Sammy G drove by, but it was likewise abandoned due to an inkling his car would be damaged without hurting anything inside. On March 2, 1978, an attempt to kill Gingello outside his favorite restaurant, the Blue Gardenia, failed. The killer, hiding in the trunk of a car in the parking lot, triggered a bomb hidden in a snow bank near the restaurant’s entrance. The explosion knocked Sammy G off his feet, but he escaped any serious injury.

Aware, but undeterred, Gingello continued his rounds making himself seen. At 1:15 a.m. on April 23, 1978, Gingello stopped at Ben's Café Society on Stillson Street downtown. Along with his two bodyguards and two young nephews, this had been their third club stop. Around 2:00 AM the nephews left, and twenty minutes later, Gingello and his bodyguards walked out. Gingello got into the driver’s seat of a borrowed black Buick and closed the door. The two bodyguards got in but before they closed their doors, a bomb placed under the car was detonated by remote control.

Because they had not had time to close their doors, the two bodyguards were blown out of the automobile, the extent of their injuries being one broken foot. Gingello was not as fortunate. His right leg was blown off below the knee and his left leg was nearly severed at the thigh. His entire body was blackened from the powder of the explosion. When questioned at the scene by police, Gingello remained gangster, refusing to speak and only giving the middle finger to a detective. He was rushed to Genesee Hospital where he died at 3:35 from shock and loss of blood. With him when he died were his father and other family members.

A sordid crowd of drunks, hookers, and pimps, flocked to the scene of the battered black Buick. Women from a nearby massage parlor ran out into the cold night in their leotards to see what had happened. When police finally removed the car, twelve hours later, souvenir hunters and morbid curiosity seekers moved in to collect jagged pieces of metal and glass and even shards of flesh left behind in remembrance of Sammy G, their home town gangster.

Retribution

The B-Team believed the assassination would be enough to weaken Russotti, but it did not have the desired effect. Quite to the contrary, 'Sammy G' Gingello's death only marked the beginnings of all-out gang warfare in Rochester. Just days after the successful assassination, B-Team member Dominic "Sonny" Celestino met with A-Team representatives to negotiate an end to the war. After hours of discussions at Lloyd's Restaurant on Alexander Street, Celestino emerged with zero results and a livid group of mobsters on both sides. Refusing to back down, DiDio's men embarked on a bombing campaign, setting off more explosions at A-Team gambling parlors and social clubs throughout the city on May 19, 1978. One such incident included a pipe bomb thrown through the window of a social club ran by the late Gingello's close friend Donald Paone. The B-Team detonated more blasts that rocked various locations days later as a further fear tactic although there were no casualties.

Sensing it was time for retaliation, Russotti's A-Team struck back and on May 25th, a sniper shot B-Team member Rosario Chirico at his home. Several other gun battles and bombings followed. Police attempted to intervene by locking up whoever they could, ousting DiDio and Chirico from their hiding places in Pittsford that June, but it wouldn't be enough to bring a halt to the war. Then on July 6, 1978, B-Team leader Thomas DiDio was gunned down by a submachine gun at the Exit 45 Motel in Victor. In a further hit to his insurgents, Russotti ordered the shooting of another B-Team associate named Rodney Starkweather, which was nonfatal, shortly after DiDio's death. Law enforcement further crippled the B-Team by arresting members around the same time. Within mere days following the A-Team's assaults on B-Team members, police arrested several men with sticks of dynamite, undoubtedly foiling plots to further bomb A-Team facilities.

With the death of DiDio and the arrests of enforcers, the B-Team had been dealt a severe blow. With the B-Team unable or unwilling to continue their grab for control of the Rochester mob, the violence ceased after the shootings. But the struggle had received tremendous attention from both local and national media. Law enforcement agencies, recently having been faced with the misconduct of various members of the sheriff’s department, were determined to break the warring factions. Investigations were conducted not only into the bombings and shootings, but also into gambling, loan sharking, extortion, arson and various other mob influenced rackets. Mobsters were frequently stopped in their cars, and on more then one occasion, were arrested for carrying weapons. The B-Team was critically crippled in a string of indictments, eight members of the faction were charged on a variety of allegations including the slaying of Gingello and the bombings of the Russotti gambling parlors. Among them were Rosario Chirico, Angelo Vaccaro and Sonny Celestino, two alleged leaders of the B-Team, and Stanley Valenti. Frank Frassetto was another. Frassetto at first had been identified as a member of the A-Team, but as it turned out acted as an inside source for the Valenti group. Starkweather decided to testify against his fellow B-Team members. Of the eight named in the original indictment, all except Stanley Valenti were put on trial. In January 1980, all seven were found guilty.

The C-Team

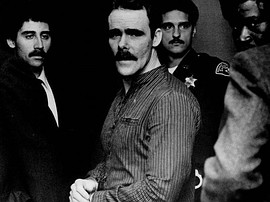

Joseph J. "Mad Dog" Sullivan was a fugitive in the 1980s wanted for over a dozen killings stretching from Rochester to New York City. As a mafia contract killer, he took the life of John Fiorino outside the Blue Gardinia in Irondequoit in 1981.

Joseph J. "Mad Dog" Sullivan was a fugitive in the 1980s wanted for over a dozen killings stretching from Rochester to New York City. As a mafia contract killer, he took the life of John Fiorino outside the Blue Gardinia in Irondequoit in 1981.

Emerging from the war victorious, Russotti regained total control over the city. Business resumed as usual for the Rochester Crime Family with gambling parlors thriving, labor unions under significant influence and money began flowing back into the family from the thriving street economy. The return of peace pleased Russotti, but he would quickly be faced with a new challenge by another internal rebellion. On December 17, 1981, Teamster's Local 398 vice president and alleged capo in the A-Team, John "Johnny Flowers" Fiorino was shot in the back of the head outside of the Blue Gardenia restaurant on Empire Boulevard in Irondequoit. A rookie police officer named Michael DiGiovanni lived right around the corner and quickly chased down the assailant who fired the bullet and escaped in a Cadillac. The two exchanged gunfire and one Louis DiGuilio was arrested. A second man fled the scene by hiding in a snowbank and escaping via the abandoned trolley tracks adjacent to Helendale Road. The initial suspect was apprehended and through fingerprints, it was later determined that infamous Irish-American mafia hitman and wanted fugitive Joseph "Mad Dog" Sullivan was the gunman who killed Fiorino. Investigators would soon learn the hit was ordered by a newcomer to the Alphabet Wars, the C-Team, led by former 'Sammy G' Gingello bodyguards Thomas Torpey and Thomas Taylor, known as "The Two Toms." Police theorized that Fiorino was murdered to prevent him from testifying to a grand jury and a federal Organized Crime Strike Force. Police believed Fiorino's murder was carried out to set an example for others and to send a message as to whose side should be chosen during the planned takeover. There were also fears Fiorino could unify the racketeers and take over the family himself as he held a longstanding reputation of being the most accessible mobster since Sammy G.

This unexpected hit caused violence to roar back to life in the Rochester underworld. "Mad Dog" Sullivan originally met Thomas Taylor during a prison stint in Attica where they formed a warm relationship. Sullivan was hired by the new C-Team, who also ordered him to kill the new underboss Richard Marino and another mobster the Toms held a vendetta against. The following several months would be a show of muscle from the physically imposing Toms. In March 1982, Taylor, Torpey and C-Team members Michael and Thomas Pelusio entered a social club and beat a man into the hospital. The beating was a clear insult to Russotti, who was linked to the club. Russotti retaliated the following month by ordering, through Rene Piccarreto, the execution of members of the insurgent faction. Nicholas Mastrodonato was murdered that same month, followed by the murder of Gerald Pelusio. Gerald was an unaffiliated brother of Michael and Thomas who police suspected had been mistaken for one of the mafioso.

Upset that his fellow A-Team members had crossed him, Russotti ordered hits on more men. Murders of several mobsters bloodied the streets of Rochester throughout the Summer of 1982. A crushing blow would soon come in court however, as police carefully used evidence, this time from legitimate means, to deliver indictments.

Indictments & Further Struggle

On November 10, 1982, boss "Red" Russotti, consigliere Piccarreto and eight others were handed federal RICO indictments. Federal officials charging them with a wide variety of crimes, including murder. All of the ten mobsters indicted made bail and were soon back on the streets. So were the Two Toms, and it did not take long for the Alphabet Wars to resume.

On April 13, 1983, Thomas Marotta, another of Russotti’s capos, was shot seven times outside of an Irondequoit apartment buildling but survived. The murder of a man named Dino Tortarice in August that same year was thought to have been Russotti’s reprisal. Tortarice’s involvement with the C-Team appears to have been minor, having been described by a police informant as “a possible associate of Thomas Pelusio”. His family and friends described him as a well-liked character, with absolutely no involvement with organized crime. However, at the time of his slaying Tortarice had been under investigation by a Federal Grand Jury in connection with the shooting of Marotta four months earlier. Marotta would be shot at again in November, and again survived.

The Mafia Dismantled

The government had begun its assault on the Rochester Family with two RICO trials during the 1980s. In the first trial, the indicted were Russotti, Piccarreto, Marotta, Joseph R. Rossi, Anthony M. Colombo, Donald J. Paone, Richard J. Marino, Joseph J. Trieste, Joseph J. La Dolce, and John Trivigno. All, or part, of this group were indicted on the following charges: operating an "enterprise" which was engaged in a pattern of racketeering activity; the murder of "Jimmy The Hammer" Massaro, the attempted murder of Rosario Chirico; the attempted murder of Dominic Celestino; the murder of Thomas Didio; the attempted murder of Angelo DiMarco; obstruction of justice; extortion of the Caserta Social & Political Club; extortion of the Young Men's Social Club; attempted arson; and several "overt acts." Assisting in the prosecution would be key government witnesses Angelo Monachino and Tony Oliveri who were both made members of the mafia cooperating with authorities. They outlined in chronological order, the events in question and placed all blame on the indicted mafiosi. On October 30, 1984, all but three of these men were convicted, including Russotti and Piccarreto. Unable to escape legal trouble themselves, the Two Toms were also reigned in by authorities. The getaway driver of the Fiorino hit, Louis DiGiulio ended up cooperating with police and confessed to everything, placing blame on Torpey and Taylor who were indicted on that killing in 1983. Initially a mistrial, the two Toms were convicted and served lengthy prison sentences in August of 1985, effectively beheading the Rochester Crime Family and putting an end to a street war triggered by the Massaro hit twelve years prior.

Attempt To Rebuild

Amico became the de facto leader of the mob after the leadership was sent to prison.

Amico became the de facto leader of the mob after the leadership was sent to prison.

With Russotti’s and the rest of the Family’s hierarchy sent to prison, again the Rochester Mafia was left leaderless. Senior members left on the streets were either unable or unwilling to take over the reigns and leadership fell into the hands of a younger generation of mobsters. Having stepped up as acting boss, according to informants, was Angelo Amico. He was aided by appointed underboss Loren Piccarreto. Both were sons of former Mafia leaders. Angelo the youngest of the late Pasquale who led Rochester before Valenti, Loren the only son of the jailed consigliere Rene. It made them familiar with the workings of the local mob, a “quality” they could use in rebuilding its former operations. Due to both the internal strife and the successful prosecutions of several members and associates, the Family’s influence had waned tremendously.

Despite their attempts to rebuild the family, Amico and Piccarreto were unable to achieve much. They did succeed in some extortion and gambling, albeit at a far smaller scale than what would've been seen just a few years prior. The grip the mafia had over illegal gambling seemed to loosen as recorded conversations included the new leaders discussing some gamblers not paying a percentage to the family. No violent action was taken to address this. To their credit and perhaps most notably, the duo was able to pull the strings of Teamsters Local 398 showing the labor union control was still widespread. This was not due to an insurgency though as Amico and Piccarreto were just an extension of the original mob leaders of the A-Team. Despite the inroads they were able to make, the two men were not quite crafty enough to avoid persecution. Almost immediately following the convictions of most of Rochester's mafia leaders, police bugged Amico and Piccarreto's regular gathering spots and indicted them on racketeering charges on October 3, 1987. Indicted this time were Angelo Amico, Loren Piccarreto, Joseph Geniola, and Donald Paone. All were charged with violating federal anti-racketeering laws. Amico was also charged with filing false tax returns and conspiracy to defraud the government. In late October 1988, Amico pleaded guilty to both counts of the racketeering and conspiracy indictment, and to one count of tax evasion in a separate indictment. Amico was sentenced to 14 years in prison. At the time of the arrests, Roger P. Williams, the acting U S Attorney for western New York, told reporters, "These individuals are the last remnants of what we know to be organized crime in Rochester."

By 1990, the Rochester Mafia was reduced in both size and influence to little more then a street gang. Members and associates still alive and out of prison were either inactive or seemingly lacking supervision. Gambling and several other rackets still flourished in the Rochester area, but were no longer controlled or influenced by one organization. The various law enforcement departments in Monroe County had succeeded in what little of their colleagues had. They had, despite an unfortunate start, almost completely destroyed the local Mafia organization with successful prosecutions. But as the years carried on, it became evident that a close watch was still needed.

In June 1993, "Red" Russotti, who had still been controlling the moribund crime family from prison, died of a heart attack, signaling the end of any powerful mafia in Rochester and certainly leaving the remaining wiseguys leaderless. Then in October 1993, Rochester police raided three gambling parlors. It were not the raids itself that raised eyebrows, since similar raids were common in the city. It were some of the persons involved that made people wonder if Rochester’s Mafia was making a comeback. Among those arrested was Anthony "Tony" Gingello Jr., the nephew of Salvatore "Sammy G" Gingello. Anthony Gingello himself was involved with the Rochester mob in the 1980s, however those in the know alleged that he was now the new boss of the Rochester Crime Family. This ultimately turned out to be, if not untrue, exaggerated as the 1993 raid would become one of the last signs of successful activity any organized Italian-American crime group had in Rochester.

A Failed Revival

With an independent Rochester Crime Family effectively dead, various other groups took its place, including associates from Buffalo, as well as New York City's Bonnano Crime Family.

In July of 1996, Thomas Marotta received his parole, having served more then eleven years of his 1984 sentence. Law enforcement believed that he was still considered dangerous and would quickly return to a life of crime. While in prison, Marotta had befriended Cleveland mobster Anthony Delmonti and upon their release, the two friends reconnected. Unbeknownst to Marotta, Delmonti was now an FBI informant and was sent to Rochester to monitor Marotta. It turns out the FBI was correct, however it has been argued that he may not have committed any crime if he had not been encouraged to by a government informant. Nonetheless, he did and in one incident during the Summer of 1999, Tom Marotta and Anthony Delmonti met in a hotel room to discuss the distribution of cocaine and money laundering. During that interaction, Marotta allegedly declared himself the new boss of the Rochester Crime Family and performed a ritual to initiate Delmonti into the organization with permission from Cleveland. In 2001 Marotta would be brought in on cocaine trafficing charges and sent back to jail in 2004 on subsequent charges involving other narcotics, stolen food stamps and car theft.

Anthony Delmonti was also instrumental in solving the mob-style murder of nightclub owner Anthony Vaccaro in Greece in May of 2000. Vaccaro's killer, Albert M. Ranieri would later confess to his involvement in the AMSA Heist. Delmonti also helped to convict the leaders of a cocaine ring operated by the ![]() Cleveland Mafia in Rochester that same year.

Cleveland Mafia in Rochester that same year.

Today

As of 2018, the Rochester Crime Family no longer exists. There is little evidence to suggest any large scale organized crime activity occurs in the city at all. While there are occasional busts on mafia-style operations such as 2011's arrest of Ersin "Mike the Turk" Yaman and Ismael "Junior" Cruz for operating a small enterprise of stolen goods and fraud out of a State Street pawn shop, and 2017's arrest of "Miami Dan" Elliott on illegal gambling charges, none of these are thought to be connected to any Italian-American crime group. Any organized crime activity in Rochester is believed to be either operated by decentralized gangs or small groups of individuals, almost always of various differing ethnicities, in the present day.

Historical Leadership

Boss

Leader of Rochester's Branch of the Buffalo Crime Family

-

Pasquale Amico (c.1920s–1947)

-

Costenze "Stanley" Valenti (1947–1958)

-

Jake Russo (1958–1964)

Boss of the Independent Rochester Crime Family

-

Frank Valenti (1964–1972)

-

Samuel "Red" Russotti (1972–1993)

-

Acting Thomas DiDio (1977–1978)

-

Acting Salvatore "Sammy G" Gingello (1977–1978)

-

Acting Angelo Amico (1988)

Underboss

-

Samuel "Red" Russotti (1964–1972)

-

Salvatore "Sammy G" Gingello (1972–1978)

-

Richard Marino (1978–1984)

-

Loren Piccarreto (1984–1988)

Consigliere

-

Rene Piccarretto (1964–1984)

Made Members & Associates

-

Salvatore "Sam Camps" Campanella - Made member of the mob and teamster who switched from A-Team to B-Team allegiance. Left town in 1978 to avoid assassination.

-

Dominic Celestino - Associate arrested in connection with the Columbus Day Bombings of 1970. Became B-Team leader after DiDio was killed.

-

William Constable - Associate murdered by Jimmy the Hammer under Valenti's orders.

-

Eugene DiFrancesco - Soldier convicted of the Massarro hit in 1978.

-

![[WWW]](https://rocwiki.org/wiki/eggheadbeta/img/sycamore-www.png) Anthony Gingello - Local businessman and associate arrested in major gambling bust in 1993. Assumed to have run rackets in Rocheter in the early 1990s.

Anthony Gingello - Local businessman and associate arrested in major gambling bust in 1993. Assumed to have run rackets in Rocheter in the early 1990s.

-

Sam DiGaetano - Lawyer and made member who allegedly plotted to kill Monroe County Sheriff in 1975.

-

Charlie "The Ox" Indovino - B-Team member and close friend to the powerful don Russell Bufalino of Pittston, Pennsylvania.

-

Joseph "Spike" LaNovara - Soldier and Valenti loyalist who was connected to the Massaro hit. Turned government witness.

-

Tony Oliveri - Soldier turned government witness involved in the DiDio slaying.

-

Thomas Marotta - Capo and enforcer. Imprisoned in 1984, but released in 1996. Became boss of the Rochester family in 1998 when it was no longer an independent family, but a faction of the Bonanno Crime Family.

-

Ange Monachino - Mob soldier turned government informant.

-

![[WWW]](https://rocwiki.org/wiki/eggheadbeta/img/sycamore-www.png) Joseph J. "Mad Dog" Sullivan - Notorious mafia hitman responsible for the murder of John Fiorino. Arrested in Rochester in 1982.

Joseph J. "Mad Dog" Sullivan - Notorious mafia hitman responsible for the murder of John Fiorino. Arrested in Rochester in 1982.

-

Joseph "Scales" Sciolino - Rochester mobster with ties to the Bonnano Crime Family who operated in Arizona during the 1970s.

-

Rodney Starkweather - B-Team member who allegedly bombed A-Team gambling parlors and shot in retaliation. Later turned government witness.

-

Leonard Stebbins - A-Team soldier who eventually went rogue during the final days of the mob, refusing to pay the Amico clan.

-

Dominic Taddeo - Alleged hit man for the mob. Also involved in plot to bust drug lord Carlos Lehder out of prison and sell him back to the Medellin Cartel in Colombia.

-

Thomas Torpey - Associate and bodyguard of Sammy G Gingello. C-Team leader. One of the "Two Toms."

-

Thomas Taylor - Associate and bodyguard of Sammy G Gingello. C-Team leader. The second of the "Two Toms."

-

Angelo Vaccaro - Member of the Pittsburgh Mafia who helped Frank Valenti seize control over Rochester and establish an independent family.

External links

Comments:

Note: You must be logged in to add comments